|

Digital Wireless Telephones and Hearing Aids

Reprinted with permission from Audiology Online (www.audiologyonline.com)

This article first appeared on 2/12/2001.

Linda Kozma, M.A. CED, CCC-A

Abstract:

The introduction of digital wireless technologies in the mid-1990s created a potential new barrier to accessible phone communication for hearing aid wearers. When digital wireless telephones are in close proximity to hearing aids, interference may occur. The interference may be heard as a buzzing sound through the wearer's hearing aid (Skopec, 1998). Interference does not occur with all combinations of digital wireless telephones and hearing aids. However, when interference does occur, the buzzing sound can make understanding speech difficult, communication over cell phones annoying and may render the phone completely unusable to the hearing aid wearer (Hansen and Poulsen, 1996). It's likely that hearing aid wearers will approach audiologists for information about this complex issue. This article will address many of the issues relating to cell phones and hearing aids.

Introduction

Wireless telephones are among the fastest growing technology in history. A survey by the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association (2000) estimates wireless subscription to be approaching 100 million users – just in the USA! More commonly known as cell phones, these devices are changing our culture and the way we think about telecommunications. Wireless technology is providing people with a feeling of safety and a level of convenience with telephone communication previously unknown. As prices decrease and options increase, the wireless phone may quickly become the most commonly used phone, regardless of the location or purpose of the call.

Unfortunately, new barriers to accessibility have arisen with the introduction of digital wireless technologies. Many people using hearing aids may be unable to use digital wireless telephones due to audible interference that can be created when the hearing aid and telephone are in close proximity to one another. Hearing aid candidates and wearers need to be educated about this compatibility issue. Audiologists can assist their patients by being informed about how wireless telephones work, the nature of the potential compatibility problem between hearing aids and digital cellular technology, the options for accessible wireless communication, and ways to participate in consumer advocacy.

How Wireless Telephones Work

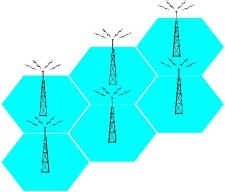

All wireless telephones work in a similar way. A given geographic region, called a service area, is divided into contiguous “cells.” Each cell contains a base station and a transmitter. Cellular service providers, such as Cellular One, AT&T Wireless, and Sprint PCS, provide wireless phone services delivered across this network. Each network uses a particular approach to transmitting telephone conversations through the air.

Cellular phone manufacturers, such as Ericsson, Motorola, and Nokia, make telephone handsets and other wireless telephone equipment. Cellular service providers select the phones that may be used on their networks. Each service provider “supports” some, but not all, of the wireless telephones on the market.

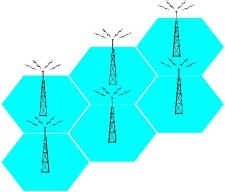

Fig 1: A service area is divided into contiguous cells each containing a base station with a transmitter.

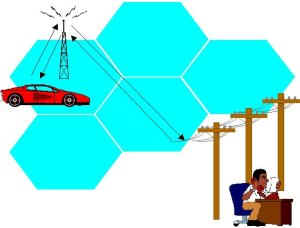

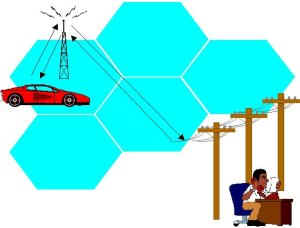

When a service subscriber places a call, the “cell” phone communicates with the nearest base station in its network and the base station communicates with the receiver’s phone network. As the caller moves from one cell to another within the network, base stations communicate with one another and “hand off” the call. In turn, the wireless network hands off the call to the wire line network. When a subscriber moves out of the immediate service area of the provider, the phone will begin to “roam” using the base stations of another company by prior agreement.

Fig 2: When placing a wireless phone call, the cell phone (in the car) communicates with the nearest base station in its network, and the base station communicates with the receiver's phone network.

The Nature of the Problem

There are two common methods of coding speech and transmitting wireless telephone conversations: analog and digital.

Analog

Analog coding methods were used in the first cellular networks introduced in the early 1980s. These networks developed quickly, and within a short period of time covered most areas across the continental USA.

Analog coding involves making an electronic copy of the speaker’s voice. This electronic copy is transmitted between the cell phone and base station and across the network using radio waves - not unlike the way radio stations transmit music and talk programs to portable and car radios. While the analog cell phone is in communication with the analog network, an electromagnetic field is present around the antenna of the phone. This electromagnetic field does not present any inherent barriers for people using hearing aids.

Analog service is still available in some locations, but it is considered somewhat obsolete and many carriers no longer offer it. Wireless service and phones, like television, video formats, and hearing aids, are gradually changing from analog to digital technology.

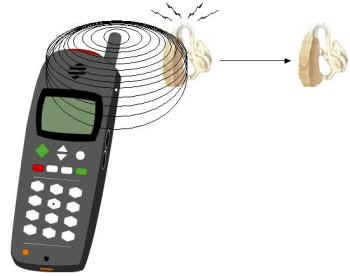

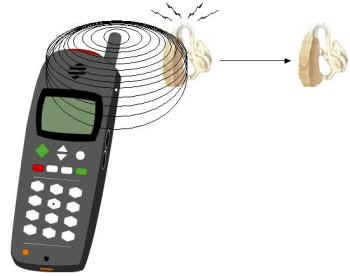

Fig 3: An electromagnetic field is present around the antenna of a wireless phone. This field pulses during communication over a digital wireless phone.

Digital

Digital technology has many advantages over analog technology, and is growing quickly. Digital allows for a larger number of users, lower service fees, higher sound quality, reduced background noise, and more secure conversations. Digital technology also supports more calling and “data” services, from “call waiting” to e-mail access and Internet browsing. However, because these newer digital networks are still being built, their network coverage is generally not as extensive as the analog network. Digital phones offer additional features such as e-messaging capabilities and demand less “drain” on batteries, but typically cost more than analog phones.

Despite their advantages, digital wireless telephones and service have a potential inherent drawback for people who use hearing aids. Digital technology codes and transmits the telephone conversation differently than analog technology. Digital coding interprets and presents the speaker’s voice as a series of numbers, 0’s and 1’s. The digital code is transmitted between the cell phone and base station and across the network using radio waves. When the digital cell phone is in communication with the digital network, the electromagnetic field present around the phone’s antenna has a pulsing pattern (Kuk and Nielsen, 1997). It is this pulsing energy that may potentially be picked up by the hearing aid’s microphone or telecoil circuitry and heard as a “buzz.”

Fig 3a: As the distance between the hearing aid and the digital cell phone's antenna increases, the interference heard by the hearing aid wearer will be reduced or eliminated.

To further complicate matters, there are different types of digital technology. The most common technologies are CDMA (code-division multiple access) and at least three varieties of TDMA (time-division multiple access) called TDMA, GSM, and iDen. Almost all service providers have selected one digital technology for their networks. For example, Verizon Wireless and Sprint PCS use CDMA technology; AT&T Wireless uses TDMA; VoiceStream uses GSM and NexTel uses iDEN.

The exact type of digital technology and several other factors can affect the sound quality and loudness of the interference. For example, the interference resulting from one type of digital technology is sometimes described as “sounding like a motorboat” while another is described as “sounding like a bumblebee.” Power requirements for transmission will affect the loudness of the interference. Power requirements increase as the distance between the cell phone and base station increases, causing the strength of the electromagnetic field around the phone’s antenna to increase.

Audiologists should encourage hearing aid patients to be persistent as shoppers. Hearing aid wearers may find one technology works better than another with their hearing aid. If they have a problem with one brand of service, encourage them to try another. There is anecdotal evidence that CDMA service causes less audible interference than the TDMA technologies. Audiologists might suggest that their patients start with this technology whenever the option exists.

Solutions: Working Toward Compatibility

Solutions to the compatibility problem between digital wireless telephones and hearing aids originate from a number of different arenas.

Phone Solutions

Solutions from the telephone industry may include; reducing the strength of the pulsing electromagnetic field on hearing aids by increasing the number of base stations, improving antenna technology and shielding the phone. Handset design may be an important phone feature for hearing aid wearers consider. “Flip” phone antennas are somewhat further from the ear (and the hearing aid) during use than standard bar style phone antennas. The increased distance between the hearing aid and the phone’s antenna may reduce or eliminate the effects of the interfering energy field (DELTA, Telelaboratoriet, RNID and The Mike Martin Consultancy, 1999).

Fig 4: A flip phone (left) and standard bar phone (right).

Some phone manufacturers are already providing hearing aid compatible (HAC) accessories for people using telecoils in their hearing aids. When audiologists discuss the use of accessories with hearing aid patients, it’s important to emphasize that additional accessories usually means additional cost.

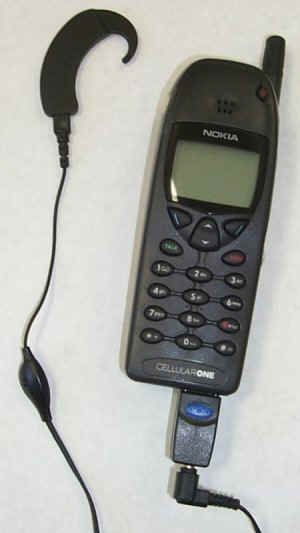

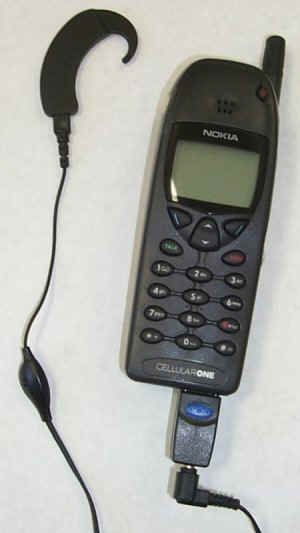

Neckloops: Three wireless phone manufacturers, Nokia, Motorola and Ericsson, have developed neckloops that inductively couple to a hearing aid’s telecoil to help keep the phone distanced from the hearing aid. The neckloops are unobtrusive accessories that plug into compatible phones. These loop sets include a built-in microphone and permit hands-free use of the phone and binaural listening if the user has two hearing aids with telecoils. The phone itself can be carried in a pocket or clipped on a piece of clothing, away from the hearing aids, so the effects of the interference are lessened or eliminated. (Note: As of 8/00, Nokia’s neckloops [models LPS-1 and LPS-3] were available for purchase in retail outlets. Motorola and Ericsson’s neckloops, new product accessories for both companies, were not yet available for retail sale.) It is important to realize that many of these systems run on button batteries. Patients need to be reminded to change batteries on a regular basis, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Picture 1: The Nokia neckloop model LPS-1 attached to a Nokia model phone.

Third-Party HAC Accessories: There are many third-party hearing aid compatible (HAC) accessories available for purchase by hearing aid wearers who have telecoil options on their hearing aids. There are devices similar to the neckloops described previously, which have a silhouette inductor that slips on the ear behind the hearing aid and produces a strong magnetic signal for pick-up by the hearing aid’s telecoil. A built-in microphone is included for hands-free use of the phone.

Picture 2: A third-party HAC accessory with a silhouette inductor and built-in microphone attached to a Nokia model phone using an adapter.

HAC headsets are available (e.g., Plantronics - M series at www.plantronics.com) in many styles and with features such as in-line volume control. There are devices designed to strap onto the phone (e.g., TELEMAX at williamssound.com) allowing the phone to work with the hearing aid telecoil. This may be particularly useful to hearing aid users who do not experience interference from digital wireless phones, but prefer or need inductive coupling for telephone communication. Built-in HAC is available in some analog wireless phones. Some digital wireless phones may also have built-in HAC, but due to potential interference problems, they are not advertised as such.

Miscellaneous Accessories: Another accessory that might reduce interference is an external antenna accessory which effectively changes the location of the antenna away from the user’s head or directs the electromagnetic field away from the user’s ear. One interesting type of device (e.g., Cell-Link at www.hitec.com) is for car use only. It plugs into a car’s cigarette lighter and uses the stereo system to pick up the telephone conversation. The output of the phone’s earpiece is redirected to the car’s speakers where the stereo’s volume and tone controls can be adjusted to improve listening. Another accessory for use in the car is a dashboard antenna (e.g., DashMate at www.cellphoneantennas.com) which also moves the antenna away from the user’s head.

Another product (e.g., PCS antenna at www.cellphoneantennas.com) slips over the phone’s antenna and directs the antenna’s electromagnetic field away from the user’s ear. This type of accessory may be helpful to some hearing aid wearers who use the microphone setting on their hearing aid for phone calls. It probably will not be as effective for telecoil users, since some of the interference with the telecoil comes from other circuitry inside the cell phone and not just from the phone’s antenna.

Finally, there are companies (e.g., AegisGuard at www.goaegis.com) manufacturing phone guards that shield cell phone users against the electromagnetic radiation they emit. This type of product has been marketed for individuals concerned about possible health risks associated with cellular phone radiation. Because the shielding directs the antenna’s electromagnetic field away from the user’s ear, it may be useful to hearing aid wearers.

Although the accessories discussed (above) may be useful to hearing aid wearers who experience interference when using digital wireless phones, there is very little, if any, independent information to support their use and relative effectiveness.

The Other Wireless Option: Analog

Some consumers won’t consider a particular hearing aid/digital phone combination to be highly usable unless they cannot detect the interference at all. The sound of interference can make communication more difficult in noisy mobile environments and situations. For these reasons, the purchase of a digital phone should be approached carefully.

At present, hearing aid wearers who experience interference may find that for a wide range of situations, a hearing aid compatible (HAC) analog phone works best. Analog HAC phones are available through wireless telephone manufacturers, and analog phones modified to be HAC are available through Audex, Inc. However, it is important for the patient to understand that market trends suggest digital wireless service and phones will be the only technology choice available within a few years. Even now, many carriers do not offer analog service, and fewer analog phones are available for purchase. For this reason, it is worthwhile to encourage your patients to investigate digital services and options to see if these technologies can work for them.

“Dual mode” phones can operate on both digital and analog technology. However, they are generally not an alternative for individuals who want to exclusively use analog service. On almost all dual mode phones, the network, rather than the user, selects which technology will be used on a given call. Dual mode phones were developed so that digital service subscribers could still use their phones while traveling in areas where analog, but not digital service, was available.

Hearing Aid Solutions

Some hearing aid manufacturers are working to increase hearing aid immunity to electromagnetic interference through shielding and circuit modification and design and have marketed products advertised with this characteristic. It should be noted that behind-the-ear hearing aids seem more susceptible to interference than in-the-ear hearing aids and custom canal aids (Ravindran, Schlegel, Grant, Matthew and Scates, 1997). The smaller aids are worn farther away from the phone’s antenna, are shielded by the user’s head and may have less gain. Digital hearing aids also seem to resist interference better than their counterparts using analog circuitry.

Audiologists may want to suggest hearing aid candidates select hearing aids with built-in immunity and t-coils, especially if their patients have an interest in or need for using digital wireless telephones. T-coils are required to take advantage of many of the accessories being developed by both the phone industry and third party manufacturers. Hearing aid wearers should ask cellular service providers about the type(s) of technology (digital or analog) they use. If hearing aid wearers use a telecoil for telephone communication or have a telecoil-equipped hearing aid(s), the audiologist might suggest that the patient ask which phones are adaptable for use with HAC accessories. If hearing aid wearers use the microphone setting on their hearing aid for telephone communication, the audiologist might suggest they try using hands-free headsets with or without their hearing aid(s). If they have direct audio input (DAI) capability on their hearing aids, hearing aid companies (e.g., Oticon) may be able to alter the connection to their DAI boots using the phone’s hands-free ear bud/microphone accessory to provide more accessible ‘cell’ phone communication.

Picture 3: A Nokia digital cell phone hands-free (ear bud) kit modified for direct audio input (DAI) to an Oticon hearing aid.

If possible, the consumer should shop at the retail store of the service provider (e.g., AT&T Wireless). Telephone store sales personnel often know more about these issues than sales personnel at electronics or office supply stores. If hearing aid wearers want to use digital technology, they should ask for a trial period before signing a service contract so a large investment is not made without knowing whether the phone works with their hearing aid.

Standards Solutions

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) set up a committee to develop a standard addressing the compatibility problem between wireless telephones and hearing aids. The work to develop the standard has been ongoing for several years and is now nearing completion.

The proposed standard categorizes both phones and hearing aids based on the independent measurement of each device. The electric and magnetic fields associated with telephone handsets, and the immunity of hearing aids to these electromagnetic fields will be measured. Based on the results of these measurements, telephones and hearing aids will be placed in one of several device categories. Each telephone and hearing aid category has a corresponding number.

When the number for a given telephone and the number for a given hearing aid are added together, the resulting number will provide a prediction of the expected level of performance (the interference generated) by that combination of telephone and hearing aid. If this approach leads to clear labeling of hearing aids and telephones, it should be helpful to both audiologists and consumers.

Consumer Advocacy

Audiologists should encourage patients to participate in consumer advocacy.

Consumer Organizations

One way to participate in consumer advocacy is by joining a consumer organization. These organizations generally produce consumer publications and may hold local and national meetings on a regular basis. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) Information Clearinghouse publishes an on-line directory of national organizations that focus on hearing health related issues (http://webdb.nidcd.nih.gov/resdir/resourc.html)

e-Sources

In an area where information is changing quickly, the World Wide Web is, of course, a valuable means of staying informed. Several websites that may be helpful in sorting out wireless service providers and telephones include http://www.wirelessadvisor.com, www.decide.com, and www.ephones.com. The Wireless Advisor gives basic information about wireless telecommunications and links to companies and helps identify which service providers operate in a particular area. Decide.com allows you to view the coverage areas provided by various service providers and listen to samples of calls (without interference) made in your area. Ephones.com provides information on wireless technology. However, none of these sites includes information on wireless phone accessibility.

The Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association’s (CTIA) website (www.wow-com.com) provides information on accessibility and publishes a list of accessibility contact personnel in many wireless service and phone manufacturing companies. Links to manufacturers’ accessibility information are posted, making it easier for consumers to see what phone models and accessories are being offered.

With regard to the issue of digital wireless telephone interference with hearing aids, research centers’ websites and the Self Help for Hard of Hearing People, Inc. (SHHH) website (www.shhh.org) will contain updates on research and industry progress. Two center websites to consult are the RERC on Telecommunications Access (www.trace.wisc.edu and tap.gallaudet.edu) and the RERC on Hearing Enhancement

(www.hearingresearch.org).

Consumer Feedback

Audiologists should encourage patients to provide feedback to the industry and to hearing professionals and government agencies regarding their experiences with digital wireless telephones and hearing aids. Their feedback can provide all of us with a better understanding of how pervasive this compatibility problem is and to what degree the solutions work in the “real world”.

Within the cellular telecommunications industry, consumers can contact the individuals who handle disability access issues at companies providing their cellular service and their wireless phone. Within the hearing aid industry, consumers can contact the company that manufactured their hearing aid(s). Government agencies involved with these issues include the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The FCC’s Consumer Information Bureau is the Disabilities Rights Office that can be contacted by email at access@fcc.gov or by mail at FCC, DRO, 445 12th St. SW, Washington, DC, 20554. Problems with compatibility can be reported to the FDA either online or in writing through a program called MedWatch. For online access, the FDA home page is at http://www.fda.gov and click on the words MedWatch. To receive a MedWatch reporting form to fill out at home and mail back to the FDA, call 1-888-463-6332.

Some Final Thoughts

The problem of wireless telephone interference with hearing aids is a difficult one. The complexity and changing nature of service and products will complicate the audiologists’ and consumers’ challenge in understanding and managing this problem for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, audiologists are the hearing health care providers that individuals with hearing loss will likely approach with questions about digital wireless telephones and hearing aid compatibility. For hearing aid wearers who want to take the plunge into the digital wireless telephone world, encourage them to do so.

Provide your hearing aid patients with the education and training they need to be informed consumers. They may find interference does not occur with the hearing aid and the digital wireless phone they select. If your patients do experience interference, you will have provided them with a basic understanding of the nature of the potential compatibility problem between hearing aids and digital wireless phones, information about their options for accessibility, and ways to be good consumer advocates. The world of telecommunications is “going wireless and digital.” Until this technology is fully accessible to all without the need for special knowledge or accessories, audiologists have a role to play in helping hearing aid wearers and candidates take advantage of it.

The inclusion of specific products in this article is used for the sole purpose of reader education and not as an endorsement of the products themselves. A similar version of this article appeared in the November/December, 2000 issue of “Hearing Loss,” a consumer publication by SHHH, Inc.

This article originally appeared on www.audiologyjournal.com in November, 2000. Since that time, Audiology Online (www.audiologyonline.com) has acquired the Audiology Journal. This paper was re-edited and updated and appears here as a courtesy to our readers for educational and informational purposes. We are grateful to the author and the Audiology Journal for allowing us (Audiology Online) to re-publish this updated version of this article here.

References

Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association (2000). Semi-annual wireless industry survey. http://www.wow-com.com/wirelesssurvey/ (23 Jan. 2001).

DELTA, Telelaboratoriet, RNID & The Mike Martin Consultancy (1999). Hearing aids and mobile phones interference and immunity standards: Technical report TR1. http://www.delta.dk/hampiis/report.htm (23 Jan. 2001).

Hansen, M. O., & Pousen, T. (1996). Evaluation of noise in hearing instruments caused by GSM and DECT mobile telephones. Scandinavian Audiology, 25(4), 227-32.

Kuk, F. K., & Nielsen K. H. (1997). Factors affecting interference from digital cellular telephones. The Hearing Journal, 50(9), 1-3.

Ravindran, A., Schlegel, R., Grant, H., Matthews, P. & Scates, P. (1997). Study measures interference to hearing aids from digital phones. The Hearing Journal, 50(2), 32-39.

Skopec, M. (1998). Hearing aid electromagnetic interference from digital wireless phones. IEEE Trans Rehabil Eng, 6(2), 235-9

Back to home page Back to home page

|